If I were to ever write a memoir (and I’m not planning on it, by the way), there would be two chapters devoted to two of the most significant experiences and periods of my life.

First was my time spent working as an MHT (Mental Health Technician) on the adolescent ward of a private psychiatric hospital outside of Philadelphia. It was the mid-1970’s and the mental health profession was dangling on the tail end of its “One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest” period in terms of diagnosis and treatment. Patients were labeled, largely misunderstood, locked away, drugged, and monitored. I remember my time spent working with schizophrenic, manic-depressive, and psychotic teenagers as one largely void of hope. The fact that a sedated existence was the best scenario for a group of kids almost my age did a real number on me. I loved my job. I loved loving these kids. But there was no love at all between me and the reality I faced for eight hours a day in that dark place. In fact, the experience was so void of hope that during my second summer as an MHT, I spent my days fighting a growing stomach-ache that had me spending many of my hours at home doubled up in bed. My nerve and stress-induced gastritis went away when I returned to school in the fall, but the memories of what I saw and experienced have never left.

Of course, since then, new technologies have allowed scientists to map and understand the wonders and complexities of the brain, along with many of the malfunctions that the fingerprint of human depravity have left on this organ that once was all that God intended it to be. In hindsight, I know that my young friends could only be diagnosed and treated based on a limited body of knowledge. In today’s world, those same kids would have the advantage of better diagnosis and treatment. But doing the best with what was known at the time, a small army of adolescents walked back and forth in a locked ward, prisoners to their sickness. . . . with the seen and unseen “locks” of their lives serving as loud and clear cries for the Kingdom of God to come and undo what sin had done.

The second period took place a few years after my time at the psychiatric hospital. Newly married, we had moved to the north shore of Massachusetts to attend Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary. The combination of academic rigor and the idyllic New England setting served to help me focus on things other than people suffering from mental illness. In many ways they were forgotten. Little did I know that beneath the appearances of a seminary community intent on pursuing a deeper knowledge and understanding of God (ie. It all looked great), there were classmates and even professors who were struggling to keep it all together.

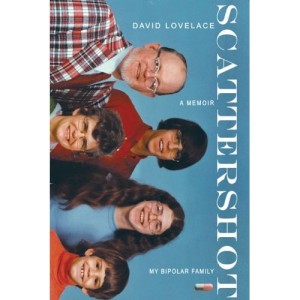

Yesterday I finished reading a brand new book that served to pull the curtain back on a reality that stood in front of us regularly in the seminary classroom, but which we never even knew existed. David Lovelace has written a compelling memoir, Scattershot: My Bipolar Family (Dutton, 2008), that chronicles the deep and debilitating battles with mental illness that four of five members of his immediate family of origin waged back then, and even up to today.

The book caught my eye not so much because of its topic, but because of one of its principal subjects, David’s father Richard. When I arrived on the Gordon-Conwell campus in 1982, Richard Lovelace was one of the most beloved professors and a well-known champion of the truth in evangelical circles. He had written one of the most widely-read and critically-acclaimed books of the late 1970s, The Dynamics of Spiritual Life. Arriving on campus, we not only looked forward to sitting in his church history classes, but it was a treat to hear the many hilarious stories regarding Dr. Lovelace’s eccentricities and absent-mindedness. Some of them were so incredibly out there that you actually wondered if they were true, or simply legendary.

Reading Scattershot served as a catalyst for the collision of two of my worlds – that suburban Philadelphia psychiatric hospital, and Gordon-Conwell seminary. While he has seemingly turned his back on the faith in response to a combination of his own bipolar battle and the fundamentalism of his childhood, David Lovelace tells the harrowing story of his family with a combination of ugly detail, ongoing love for his parents, and grace. His father is no longer just a professor who stood in front of the class or was seen walking across campus. Scattershot reveals the depth of his humanity and struggle, as David’s writing forces readers to laugh with the family when appropriate (I learned even more about Dr. Lovelace’s experiences and eccentricities), and cry with compassion over the deep darkness of mental illness, especially when viewed from the inside out.

The book features one of those stereotypical early 1970s church directory photos on the cover (can you say “Olan Mills?”). We’ve all seen them, and most of us have been in them. . . . complete with the plaid sport coat. But there was torment lying under the surface of the five smiles, and the words hidden behind the book’s cover lay it all out in ways that will open readers’ eyes to a world that while it lives in our midst, we might never know, inhabit, or even understand.