Tuesday, May 12. It’s winter time in Rwanda. . . and it’s still hot. So hot that after a day and a half on airplanes we stepped into the nighttime heat at Kigali Airport and I couldn’t wait to get to our air-conditioned hotel room. That is. . . until I opened the door to the hotel room and couldn’t find an AC thermostat anywhere.

While my initial response to this “inconvenience” is embarrassing, it’s also quite telling. You see, I looked at Lisa as we struggled to pull our bags into the hotel room and lamented, “There’s NO air conditioning!” I wasn’t even an hour on African soil on a trip with Compassion International to meet the poorest of the world’s poor, and I was already complaining. It only took a split second for me to shift my lament from the absence of air, to the absence of compassion and other-centeredness on my part. My conscience was blasted with shame and guilt as I realized that I am a man who has steadily and slowly allowed his life to be lulled to sleep in the arms of comfort, material abundance, and lack of want. I looked at Lisa and said something like, “Listen to me complaining. What’s wrong with me? These people don’t have food, and I’m complaining about no air.” I soon realized that the screen in the window and the fan on the floor were excessive luxuries.

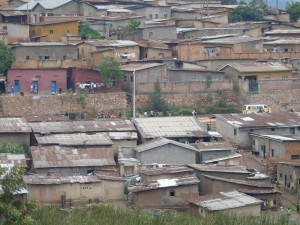

Part of my problem is that I’m not Bill Gates or Donald Trump. That fact has allowed me to somehow believe that I identify more with the poor than with the rich. Line me up with all Americans from richest to poorest and I’m not anywhere near the front of the line. There are millions and millions of people between me and the aforementioned big boys. But line me up with the world’s population and I’m in the top two or three percent. . . . far, far ahead of the poorest of the poor whose mud, dung, and corrugated metal shacks I was soon to visit for the first time in my life. I pay more over the course of a year for the cup of coffee I drink every morning than they make during the same 365 days.

Prior to our trip I had asked the Lord to do what he wills in my life. It was beginning as we set foot in Rwanda.

My first impressions of Rwanda? First, there was the smell. It’s not bad. It’s just different. The smell of smoke permeates the air. That smell originates in the simmering wood and charcoal fires that the overwhelming majority of Rwandans use to cook their food in their outdoor “kitchens.”

Then, there was the gnawing sense that I was walking on ground where over a million people were macheted to death just 15 years earlier. Everywhere I looked I wondered what the landscape I was seeing now looked like back then. Was it littered with bodies like all the photos I had seen? How much blood does this soil hold? I also wondered what kind of pain and memories were entrenched behind each set of Rwandan eyes I saw. I found myself silently asking, “Is that person a victim or perpetrator?”

In preparation for this trip I had read more about Rwanda and the horrors of the 1994 genocide than I had anything else. Those who know me know that I tend to to think and talk quite a bit about human depravity. It’s not a morbid fascination that I have. It is, quite simply, a desire to remember things about myself and the rest of humanity that we so easily forget. We tend to think more highly of ourselves – individually and collectively – than we ought. And once we forget about depravity, well. . . that’s when we start getting in trouble. There’s no need to be diligent with ourselves, and there’s a diminishing need for divine grace and the Savior. Idolatry quickly creeps in and we find ourselves locked into a type of American Christianity that Tom Sine so accurately describes as the American Dream with a little Jesus overlay.

I believed that with my focus on the genocide I would arrive in Rwanda with eyes more keenly able to be aware of this place somehow being darker than others. That wasn’t the case at all. Rwanda is beautiful. It’s known as “the land of a thousand hills.” One of our newly-made Rwandan friends informed us upon our arrival that it’s also “the land of a thousand smiles.” Both descriptors are accurate. The people are equally beautiful. In only a few short hours I had to remind myself that while there was little or no visible evidence of the genocide and the evil at its root, what happened 15 short years ago in and among the people in whose midst we were walking is evidence that depravity is universal, it can rear its ugly head at any time in the most extreme ways, and that the genocide that happened there could happen anywhere and be perpetrated by anyone.

After a late dinner with our team, I went to bed pondering what the days ahead would hold. I was in Africa. . . . hard to believe. Already I had learned that the people of Africa are people. As I laid down and put my head on my pillow, I was acutely aware of my need to give thanks for things that the people I would meet in the morning didn’t have. . . a soft bed, a lock on my door, a full belly, a pillow, clean sheets, running water, a screen in the window, and the luxury of a three-speed fan. Sure it was sticky and hot. But shame on me.

And Mosquito nets… I camped in the states during the summer and mosquito’s were a pest and a nuisance. In Africa, at least in Uganda where I visited, Mosquito’s carry death. The shame is not in looking for A/C, but that our culture has conditioned us to expect A/C wherever we are. Instead, you’re taking God – or He is taking you wherever He is. It’s a great reminder that wherever we go, God is there – especially in 1000 smiles! Praying for you & Lisa.