One summer evening when my son Josh was only about five years old, he and I were driving east just as the sun was going down. After looking out the back window of the car at the setting sun, he leaned up and looked into the sky to see the moon. After another look back at the sun and a look ahead at the moon, he turned to me and asked, “Hey Dad, how come when the sun is still out the moon is up too?” Good question. After thinking a bit, I explained that God made the world so that there would always be a light to shine, one during the day, and one during the night. Then, I stepped down to his level and said, “And he made it so that when Mr. Sun is ready to go to bed, Mr. Moon is already up and ready to take over.” After catching a couple more curious glances at the sun and the moon, my little boy turned to me and adoringly said, “Man dad. . . . you know everything!”

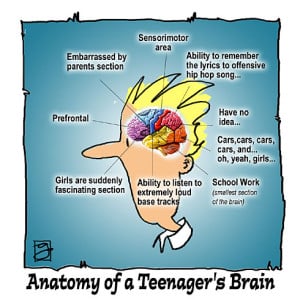

And then he grew up and turned into a teenager. Suddenly, I knew absolutely nothing.

Why did Josh’s perspective on my intellectual capabilities do an about-face? We can better understand some of the intellectual changes in our teens by looking at the work of the late Swiss psychologist Jean Piaget, who pioneered some of the most significant research in the area of child and adolescent intellectual development. Piaget found that young children pass through three distinct intellectual stages by the time they reach the age of eleven or twelve.

The first stage in the development of intelligence (roughly birth to two years) is called the sensorimotor stage, when a child’s intelligence is manifested through actions. Every parent remembers the joy of watching their child progress from acting solely on reflex to using senses to solve problems like reaching for a toy or opening a door.

The second stage in Piaget’s scheme is the preoperational stage (roughly two to seven years), when a child has the capacity to us language and play make-believe. The developing child uses imagination to pretend that a block of wood is a car or that two sticks are an airplane.

Piaget called the third stage during childhood the concrete operations stage (roughly seven to eleven years). The child is now able to think, using limited mental logic to solve simple problems. Children in this stage see tings literally and think in terms of facts. They see social problems and issues in terms of black and white, right and wrong.

The intellectual abilities of children are limited. Mom and Dad, along with most other adults, are viewed as being knowledgeable and correct on most matters. This makes life around the house fairly stable and comfortable. But things change when a child enters adolescence.

They certainly did for me when I was a teen. In hindsight, I realize that it wasn’t my parents who had changed, it was me. Although I didn’t know it at the time, adolescence had ushered me into Piaget’s formal operations stage (roughly twelve to fifteen years). I now had the ability to use more advanced logic to explore and solve complex hypothetical problems about the world on my own, and assess consequences of different courses of action. I was becoming an adult.

Amazing developments in the area of brain research are especially encouraging for parents of teens. In years past, it was assumed that a child’s brain was fully formed somewhere between the ages of eight and twelve. New scientific and research advances along with the use of Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) technologies show that the brain is an organ that grows and transitions, just like the adolescent to whom the brain belongs. The brain itself is going through a period of growth during the period between puberty and young adulthood. In addition, the brain’s hardware and software goes through a process of “wiring” or “pruning” itself during the teen years. The brain’s Limbic system is the area deep within the brain that generates emotions, including rage and fear. With hormones surging and raging during adolescence, the limbic system is affected in ways that can intensify aggressive emotions, particularly in boys. Research shows that the brain’s pre-frontal cortex is the last part of the brain to develop. This is the area of the brain that controls planning, organizing, judging consequences, decision-making, self-control, and emotional regulation. Laurence Steinberg, an expert on brain development at Temple University, says, “The parts of the brain responsible for things like sensation seeking are getting turned on in big ways around the time of puberty, but the parts for exercising judgment are still maturing throughout the course of adolescence. So you’ve got this time gap between when things impel kids toward taking risks in early adolescence, and when things that allow people to think before they act come online. It’s like turning on the engine of a car without a skilled driver at the wheel.” When all is said and done, the brain may not be fully formed until our teenagers reach the age of 24 or 25 years old!

While right is still right, and wrong is still wrong, this ground-breaking research explains a lot about teenage behavior. Teens have difficulty controlling their impulses, they lack foresight and judgment, and they are especially vulnerable to peer pressure. This may explain why teens are more prone than adults to shoplift, smoke, experiment with drugs and alcohol, ignore using their seat belts, and engage in a host of other risk-taking behaviors. Their growing and developing brains can also sustain severe immediate and long-term damage when alcohol, drugs, and pornography into their systems. Without even knowing it, many teenagers are damaging and altering their brains for life.

I often think back to my own teenage years and some of the impulsive decisions that led to saying and/or doing things that I quickly regretted. My dad would often question the root of my impulsive behaviors by asking that oft-repeated fatherly question, “What in the world were you thinking?!?” I’ve asked the same question of my own kids. Their answer echoes my answer to my dad: “I don’t know.”

While there may be marked differences in the ways that different teens view the intellectual capabilities of adults, their newfound and developing ability to think as an adult will make for some interesting conversations and confrontations at home. Sometimes the best approach is for parents to bite their tongue and understand that this is a part of normal adolescent development. Remember, your adolescent is not yet an adult. You can expect an interesting mix of adult thinking ability tainted by immaturity, impulsivity, and inconsistent logic. As someone once said, “the best substitute for experience is being sixteen!”

Wise parents learn that while it is important to continue to offer structure, Godly guidance, direction, advice, and explanations, they should at the same time give their children some freedom to make their own decisions. Some of the best lessons are learned through discovery. Your kids will appreciate this, and it will benefit them in the long run. Parents who continue to do all the thinking for their teenagers will raise children who will have difficulty making vocational, marriage, educational, time-management, ethical, and other important choices later in life. In our house, our general rule has been this: When they are children, we most often think for them. As they move into adolescence, we most often think with them. We do this so that when they become adults, they will be able to think for themselves.

As parents, encourage the use of these new intellectual capacities by doing the following:

● Challenge your teenager to reflect on issues about which you might not see eye-to-eye. Share God’s perspective by leading them to Scriptures that speak to the issue or situation. By doing so, you will model and encourage responsible and Biblical critical thinking.

● Encourage discussion, and be sure to listen before offering advice. Teenagers who sense they’ve been respected and heard, are much more prone to listen to those who have first listened to them.

● Treat your teenager as an adult whose opinions you value by allowing them an increased role in the family decision-making process.

● Always teach God’s standards of right and wrong, and be sure to explain and enforce appropriate consequences. By doing so, you will provide the structure their developing brain lacks. In effect, you will become their pre-frontal cortex!

Now that my kids are adults themselves, suddenly I’m smart again. What goes around comes around. If you are struggling with an intellectually superior teenager, trust me, there will be a day when you too will get smart again!