As a culture-watcher, I sometimes like to “rewind” as a way to gain perspective on just how much and how fast youth culture has changed. The practice serves to wake me up at times when familiarity with what was once relatively unknown lulls us to sleep because it’s become all-too-common and widespread. That creates huge problems, because we’re prone to sleep through things that are so normalized that they don’t catch our attention and wake us up anymore. One example of this is “cutting.”

A couple of years ago we recorded an episode of our “Youth Culture Matters” podcast which features a conversation with my good friend Dr. Marv Penner on self-injury and cutting. Sadly, the epidemic of self-injurious behavior that’s swept through and taken up residence in today’s youth culture is one of those things that show us just how much the culture has changed.

I first-encountered self-injurious behavior – more specifically, “cutting” – in the adolescent ward of a private psychiatric hospital back in 1974. Just a few days out of high school myself, I was hired as a well-intentioned yet terribly ill-equipped and untrained “Mental Health Technician,” working the four-to-midnight shift with a revolving cast of 15 teenagers who were dealing with a variety of psychiatric disorders. One common-thread was a tendency for them all to slice away at themselves with anything and everything sharp that they could get their hands on. Usually, it was on their wrists. That location combined with a great deal of ignorance among our professional supervisors to lead them to instruct us to chart any and every cutting incident as an “attempted suicide” or “suicidal gesture.” In hindsight, none of us had any idea at all what we were dealing with.

Fast-forward almost twenty years to the early 1990s. It was then that cutting caught my attention. . . again. This time I was studying youth culture full-time, which is why the concerned mother sent me her letter. She wrote, “I am the parent of two students who attend a local Christian school, a 15-year-old girl and a 13-year-old boy. Recently, both

A quick trip to the medical library at a local teaching hospital turned up next to nothing. . . which was still far more than I had known two decades earlier. But what was known about cutting in the early 90s was this: It was happening more frequently. It seemed to be launched as a thought or idea without outside provocation. It was usually engaged in alone for the first time by 13 or 14-year-old girls who simply had a desire to slice themselves as a result of overbearing emotional pain. Few people were doing it with the goal of taking their lives. Among those who cut, there was quite often an early experience of being victimized by sexual abuse. Once they cut, they felt better. Consequently, they cut again and again, leading to more frequent and severe episodes in an effort to achieve the end of emotional relief. Researchers also reached this conclusion: We need to learn more!

The sad reality is that since receiving that letter, self-injury has swept through youth culture like a plague. It’s not only a sign that more and more kids are hurting more and more deeply, but that cutting is no longer an unspoken and solitarily-discovered coping mechanism for those who hurt. It’s become popularized and thrust into the mainstream as an option for self-therapy and self-care through casual conversations, music, and film. In 2003, Catherine Hardwicke’s poignant film, Thirteen, depicted 13-year-old Tracey’s venture into the world of coping with a chaotic and confusing transition to adolescence through cutting. A few years ago, the always-relevant Pink took music-fans into the bathtub of a teenager who cuts in the video for her chart-topping song, “F___ing Perfect.” These depictions and others stand as brutal reminders of an increasingly mainstream reality many of us would rather ignore.

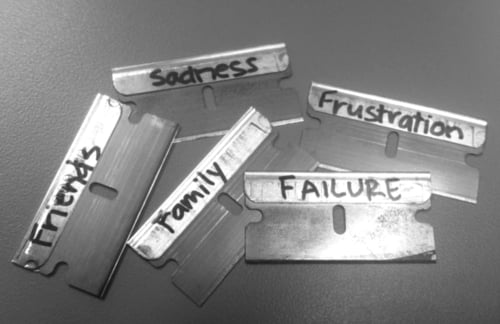

One cutter says this about a habit that, for those who don’t do it, seems absurd: “I feel like there’s something terrible inside me that I have to get out any way that I can. I think that’s part of the reason why I have to bleed. Afterwards, I feel cleansed. I feel like whatever was crushing me before has been removed. I feel calm and in control.” Beneath his shirt, unbeknownst to even his closest friends, this twenty-year-old wears the cries of his heart and soul on his chest. Because these marks are usually outward manifestations of inward pain, one researcher has called self-injury “the voice on the skin.

I want to invite all of you who know and love kids to learn as much as you can about cutting. While there are a growing number of helpful resources out there, let me suggest three. . .

Second, I also highly recommend Marv’s book, Hope and Healing For Kids Who Cut. This is a book that should be on every youth worker’s shelf. . . as one day, you will need it.

Finally, here’s a helpful free resource we’ve put together for parents and youth workers. . . “Cutting: Deeper and Wider.”