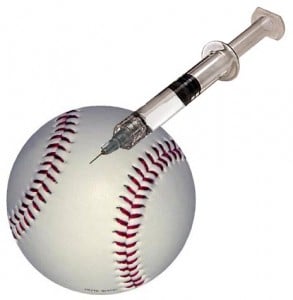

This time it was the baseball writers throwing a shutout. And the shutout was thrown against baseball players hoping to score on their eligibility for baseball’s Hall of Fame. It’s a complex process and formula that takes too long to explain here. But guys like Hall-of-Famer and old-timer Al Kaline believe that the process worked this time around, making the shutout a good thing. Kaline, like many of the rest of us, think that if a player has inflated their ability and statistics by inflating themselves with steroids – something that happened in what is now being called baseball’s “steroid era” – then you don’t deserve a spot among baseball’s greatest. After yesterday’s results (or non-results) were revealed, Kaline said, “I’m kind of glad that nobody got in this year. I feel honored to be in the Hall of Fame. And I would’ve felt a little uneasy sitting up there on the stage, listening to some of these new guys talk about how great they were. . . I don’t know how great some of these players up for election would’ve been without drugs. But to me, it’s cheating.”

Think about Kaline’s last few words. . . “to me, it’s cheating.” They’re quite telling. We live in a day and age where the definition of cheating is up for grabs. The line on what constitutes cheating is fluid. No longer is there a commonly held standard to which we can all appeal and judge both our own behaviors and the behaviors of others. That’s a sign of the times. The debate in baseball isn’t so much about whether or not the guys who got shut out (Clemens, Bonds, Sosa. . . ) used steroids, but if their steroid use was wrong.

That debate, sadly, is going to continue for awhile. My guess is that sooner or later standards will loosen and behaviors will be forgotten, even before people think to forgive them. In the meantime, I think it’s good to use this story as a prompt for discussions on cultural attitudes and personal behavior. You see, whether or not we think these guys were right or wrong, they did serve as heroes and role models to an entire generation of kids. . . mostly boys and young men. And when young dreamers stand on the diamond pretending to be Barry Bonds, the emulation usually extends beyond what the guy could do with a bat and a glove. Our heroes and role models are complete people, meaning that there’s always much more to them than who they are when they’ve got their uniform on. In fact, they spend most of their time out of uniform. . . and in our media-saturated world, that time is spent in front of a watching world almost as much as when they’re on the field.

The good news on kids and ethics is that there seems to be a decline in lying, cheating and stealing for the first time in ten years. In their latest edition of their annual survey of high school students, the Josephson Institute of Ethics tells us this:

- In 2010, 59 percent of students admitted to cheating on an exam in the last year. In 2012, that rate had dropped to 51 percent.

- Students who said they had lied to a teacher in the past year about something significant dropped from 61 percent in 2010 to 55 percent in 2012.

- In 2010, 27 percent of the students said they had stolen something from a store in the past year. In 2012 that number dropped to 20 percent.